In May, Laura presented some new research at the annual conference on human computer interaction (CHI) describing what the field of Human-Computer Interaction might learn from the artist network known as Fluxus. The work was a collaborative project between Laura, Kristina Andersen, Daniela Rosner, Ron Wakkary and James Pierce. The conference talks were not recorded, but you can view the transcript of our presentation below or read the paper here:

The talk starts here:

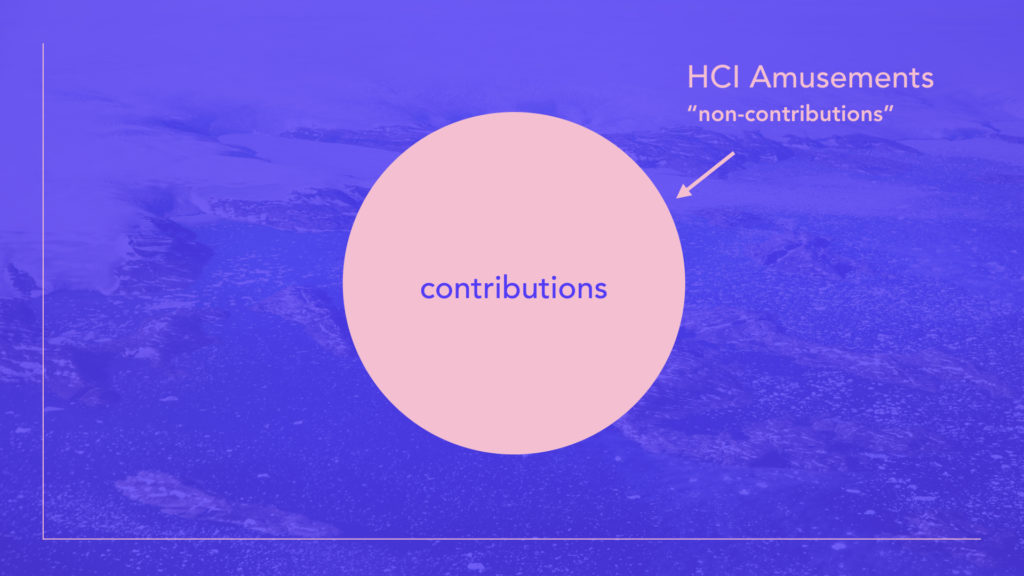

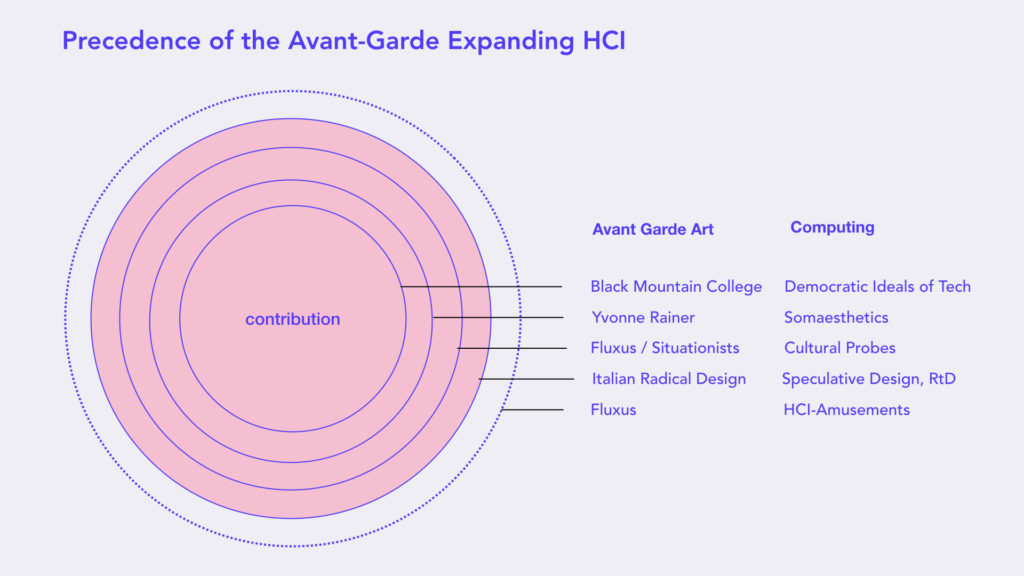

This is a formal representation of a design space. It represents the entire scope of possible questions we could be asking as a field and the practices we could be engaging.

What we consider a “contribution” to our field is only a subset of these areas. For non HCI audiences, a “contribution” is how the value of a research process and publication is assessed during peer review. The papers that are seen to make the strongest contributions to the field of HCI are selected for publication.

But one of the strengths of our field is the room it makes for broader forms of critique. Many of which are expressing that we are living in a moment where we face deeply complex and urgent challenges, leading to questioning of what counts. The methods of proof we typically rely on may be keeping us to addressing global issues and “wicked” problems in all of their complexity.

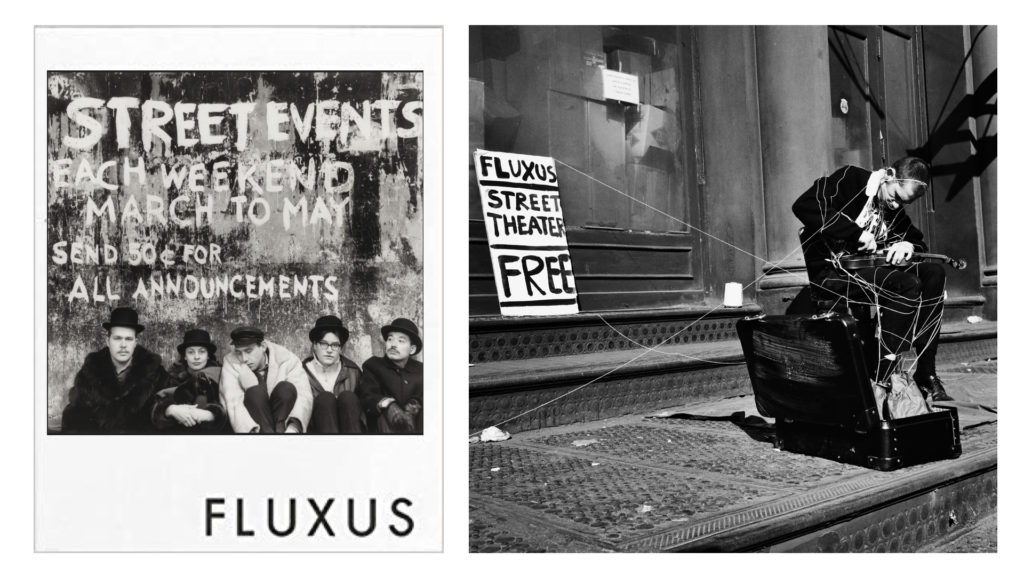

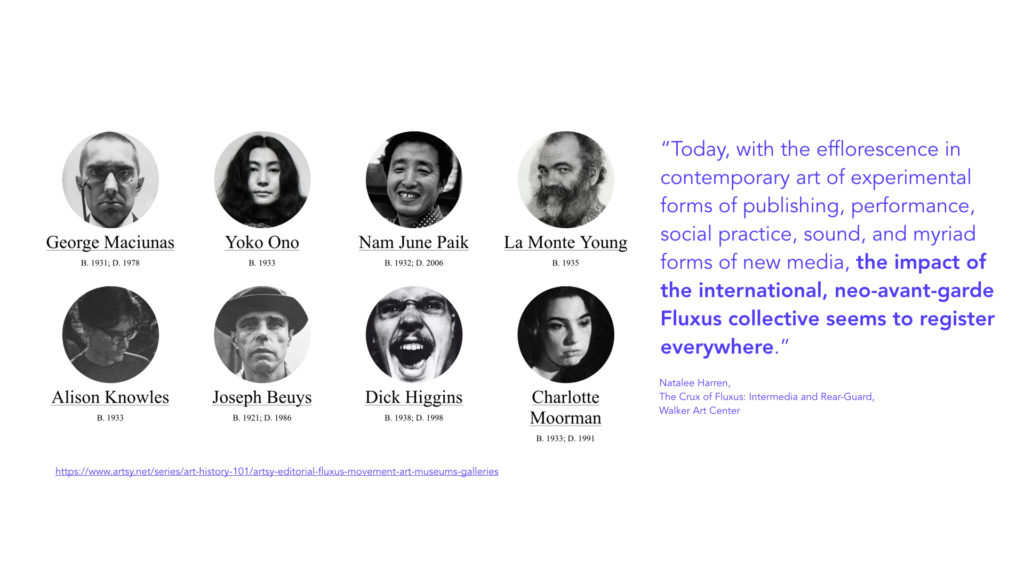

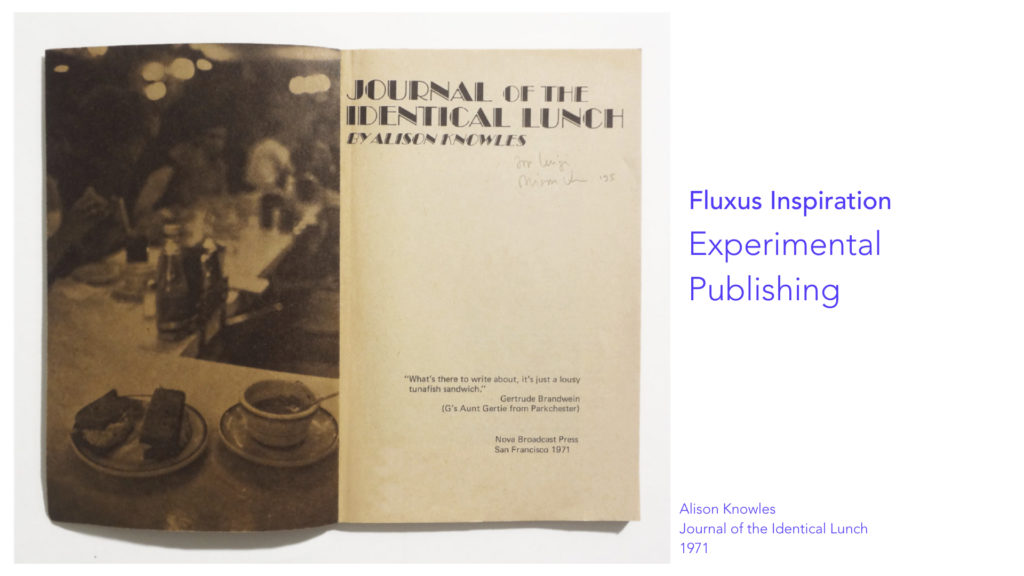

Our project asks how Fluxus, an experimental collective of artists working in the 1950’s and 60’s might help us think through and reflect on our discipline in a new way.

In the rest of the presentation, I’ll address this by attending to what Fluxus offers, how we might engage it and the expanded perspectives it can bring forth.

So lets go back to this idea that what we call a contribution is only a subset of the possible practices we could be engaging. Just as we are facing a challenge in our own notions of a contribution….

…Fluxus was confronting a challenge in what was allowed to be called “art” or what “art” practices typically described to be 1950s and 1960’s.

This piece by Rauschenberg created in ’57 is characteristic of fine art’s turn towards the use of more everyday and familiar materials as a way to speak to, reflect on contemporary culture. But Fluxus felt that this was not a true engagement with the everyday because it was still largely outside of everyday life, it was about commodity but it did not consider the more tactile and embodied modes of engaging, producing, and rethinking commodity. So they took an approach of creating “art amusements” as a means to reflecting on the boundaries and subjectivities of the fine art establishment.

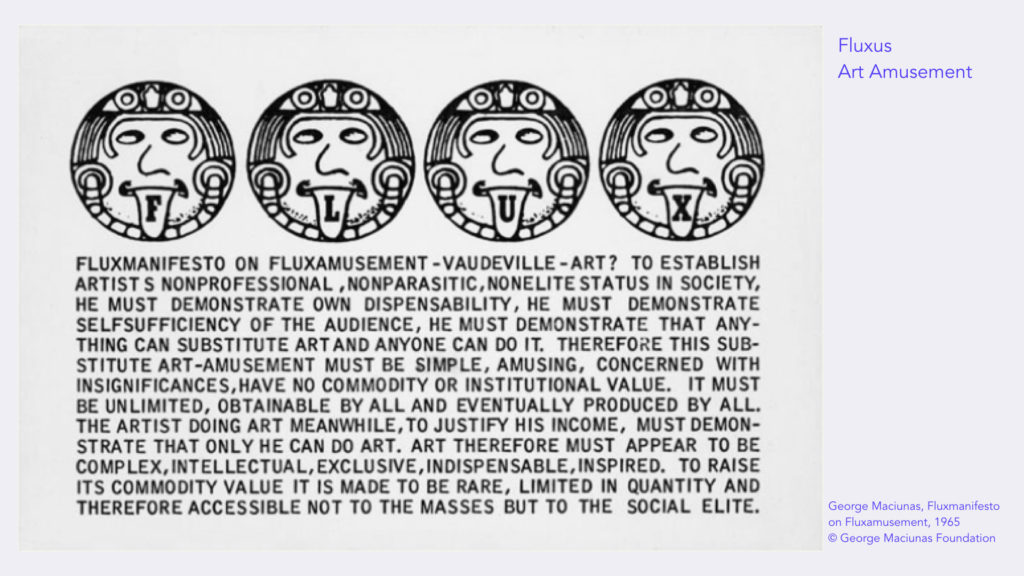

In one of their many manifestos they describe art amusement as those that:

“must be simple, amusing, concerned with insignificances, have no commodity or institutional value. It must be unlimited, obtainable by all and eventually produced by all.”

And this ideas, and the work created by Fluxus had lasting effects on art practice: the art amusements they developed have been folded into the arts establishment and had a lasting impact on an explosion of experimental and performative art practices that have taken root in the present day. As art historian Natalee Harren writes, “the impact of the international, neo-avant-garde Fluxus collective seems to register everywhere” in present day contemporary art.

Ok – so in response to what they found to be restricting and limiting in the realm of art, they created art amusements.

Along similar lines, we wondered if we could reflect on the boundaries of our own discipline by creating “HCI-Amusements” which might colloquially be understood as intentional ways of not contributing to our field.

Specifically, we ask what might we learn by trying to make something that does not contribute by traditional HCI metrics? How do we do this for and within HCI? and How does this allow us to pay attention to things in a different manner?

So now we turn to how we specifically went about engaging Fluxus within HCI, and developing different forms of HCI Amusement:

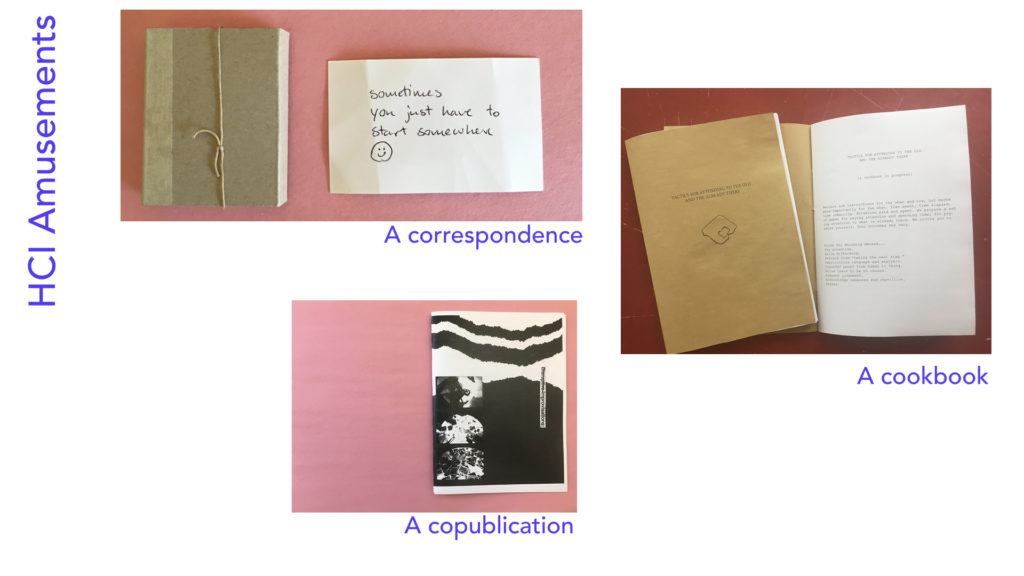

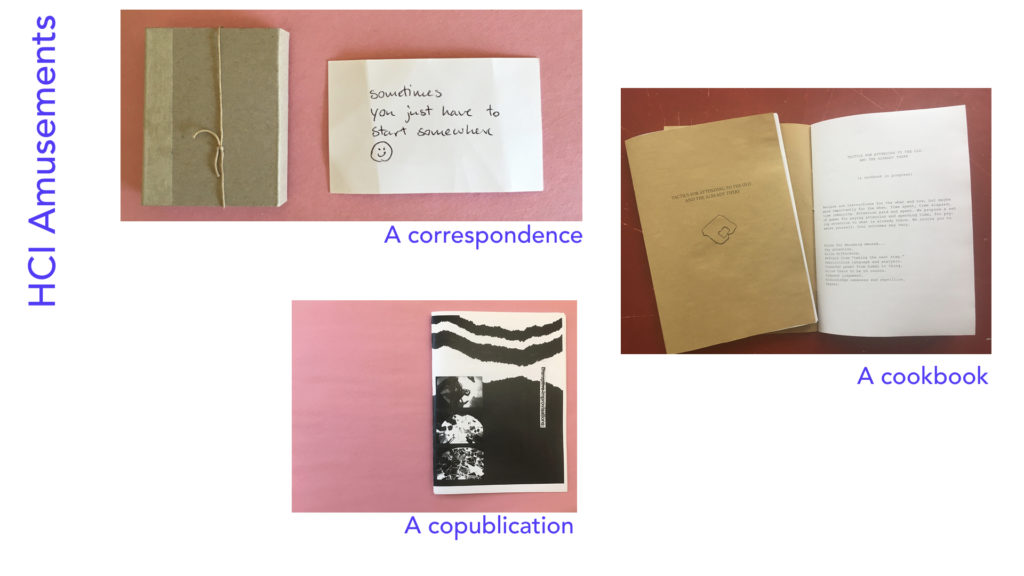

We created three kinds of HCI Amusements which we called a correspondence, a copublication, and a cookbook.

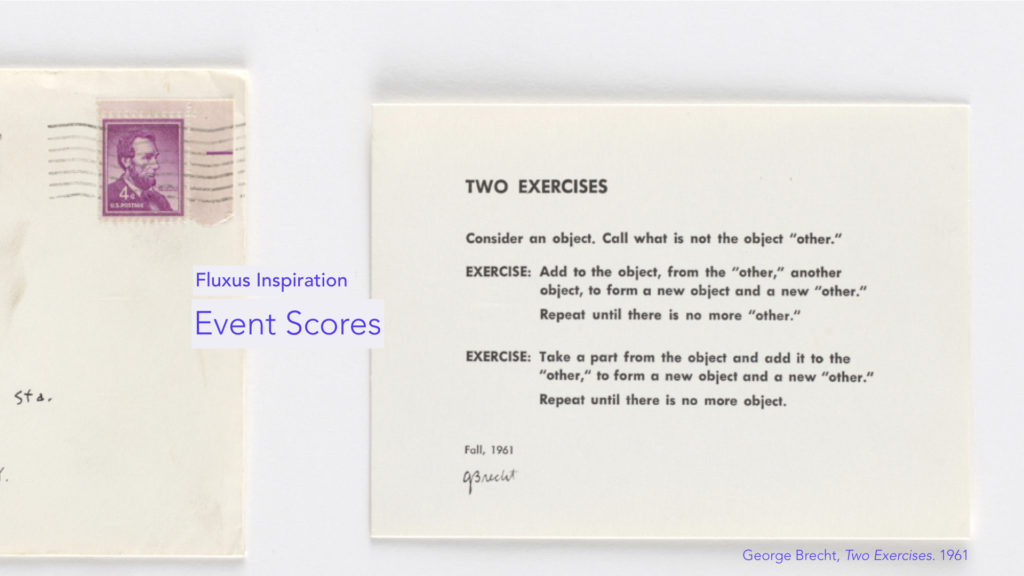

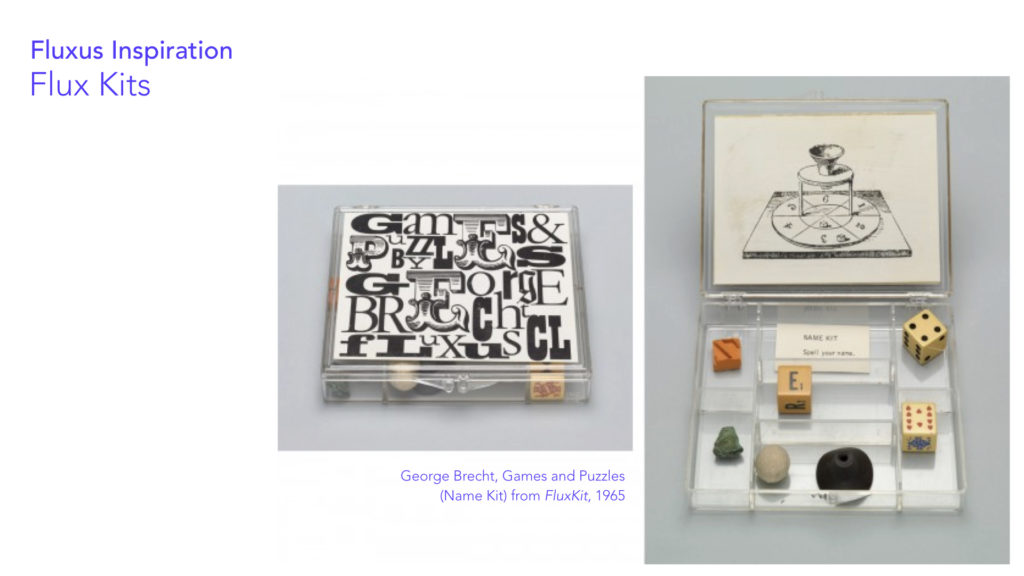

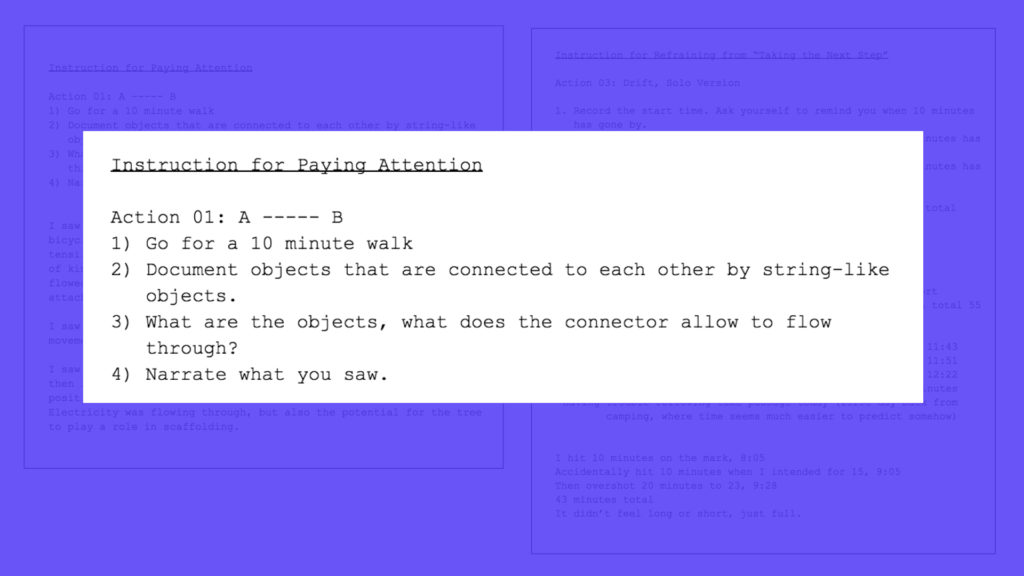

A correspondence is a structured exchange of personalized prompts for action inspired by the Fluxus Event Score and Fluxkits.

Fluxus event scores are like musical scores, but they use text as notation of activities to perform in everyday life rather than notes to play on an instrument.

FluxKits were similar to event scores as well, but they used objects instead of words, inviting the “viewer” to touch, prod, and otherwise engage the seemingly mundane materials inside.

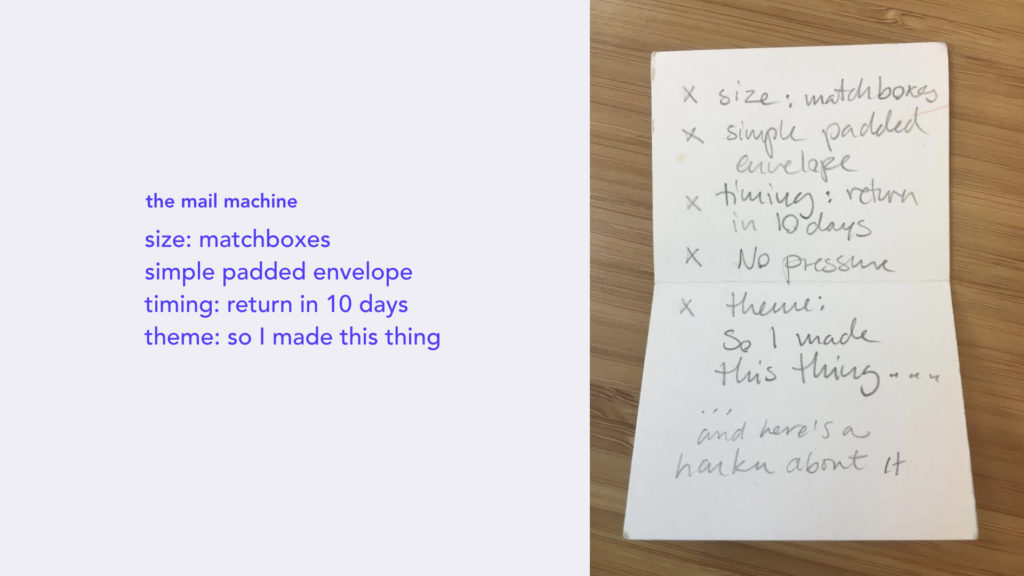

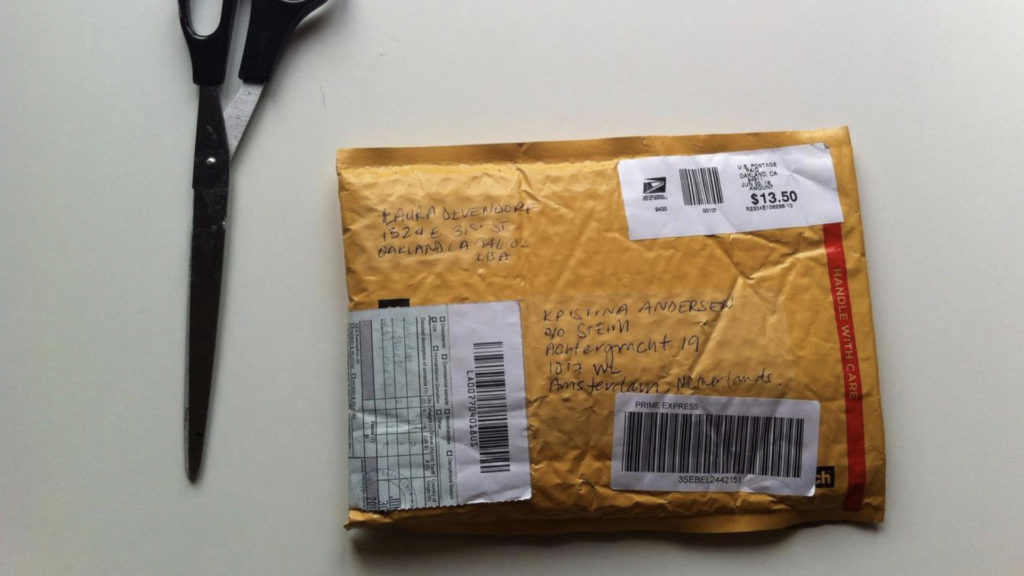

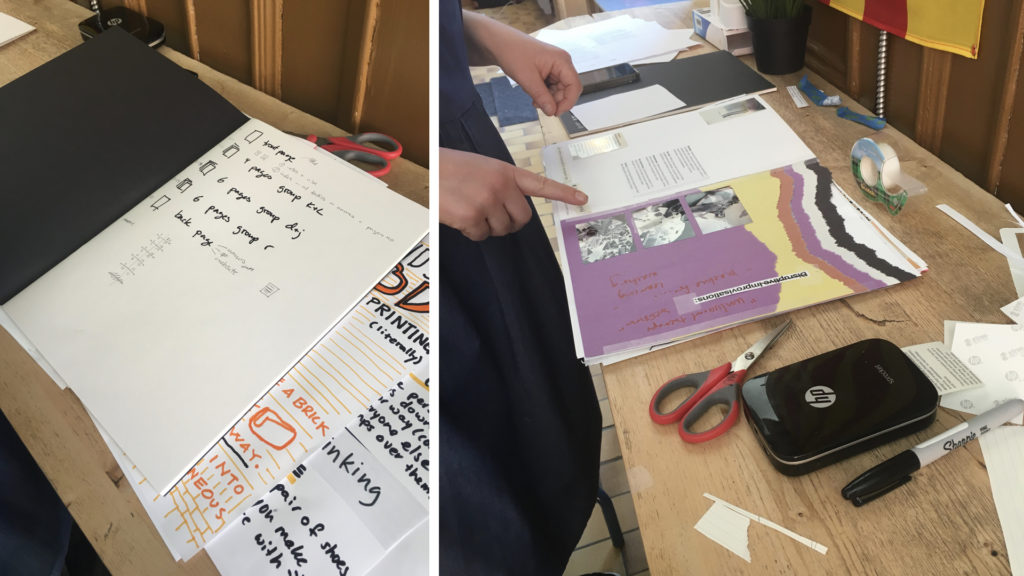

The development of our correspondence began in 2016 after we (Laura Devendorf and Kristina Andersen) talked about our shared love of flux kits. Kristina quickly drafted a set of rules for the exchange seen above.

A few weeks later I get this in the mail.

Inside of it is a collection of things…

And I make a thing from those things.

Then I refilled the box with some new items and shipped it back to Kristina.

She received it…

Unpacked it…

and made a thing…

The rules were made to be evolved based on the amount of amusement they produced. The rule to have a matchbox stayed but the return in 10 days was quickly abandoned. This exploration became an activity of looking for small things that had been left behind. We dug through junk drawers and the odds and ends just laying around to “craft” a special kit for the other. In an odd way, we began getting a sense of the other’s life by what they had to get rid of and the odd ubiquity of certain products like dessicant “freshening” packets, pencil stubs, and bits of thread.

We saw the correspondence as activating the mundane in a way that made it more noticeable and present. Something we noticed putting into our boxes would continue to become present to us in ways it hadn’t before.

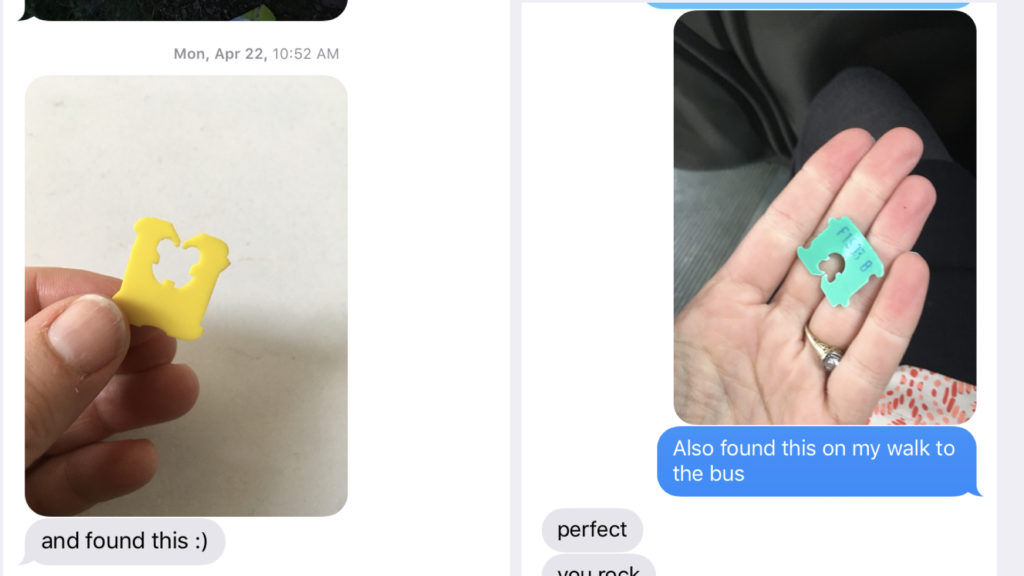

This included an odd fascination with bag fasteners that extended into our digital communications.

Check that one out!

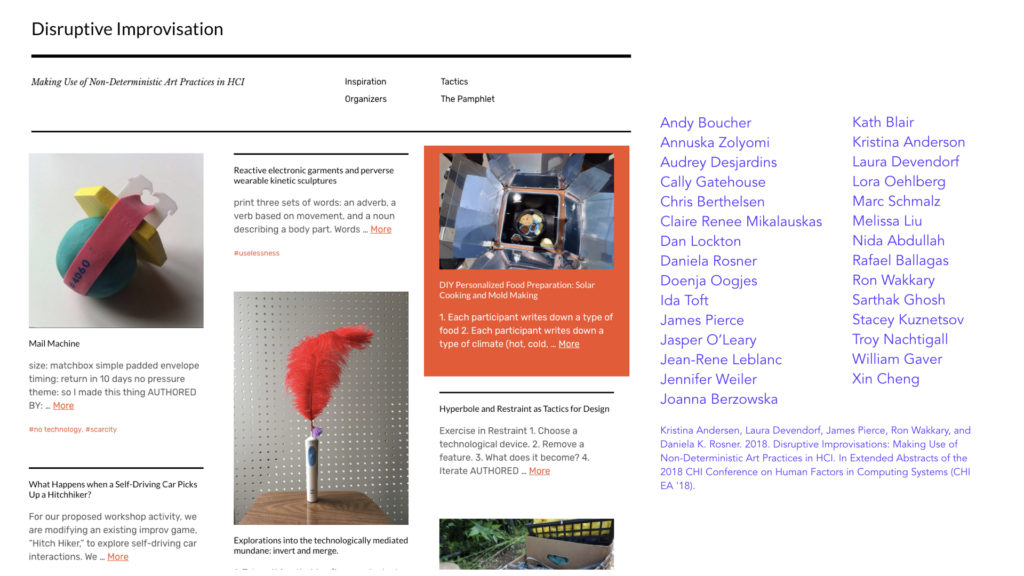

The next kind of amusement was a community exchange of prompts for making, which we did because we were curious how people in HCI might already be adopting some of these open-ended techniques in their practice.

This was particularly inspired by Fluxus texts and records published by “Something Else Press.”

We started by making a call to HCI practitioners who were interested in engaging these ideas. We made a workshop call asked people to submit “recipes for making” that were inspired by their practices. We were particularly interested in how participants might engage themes of modesty, scarcity, uselessness, no-technology, and failure through these small activities.

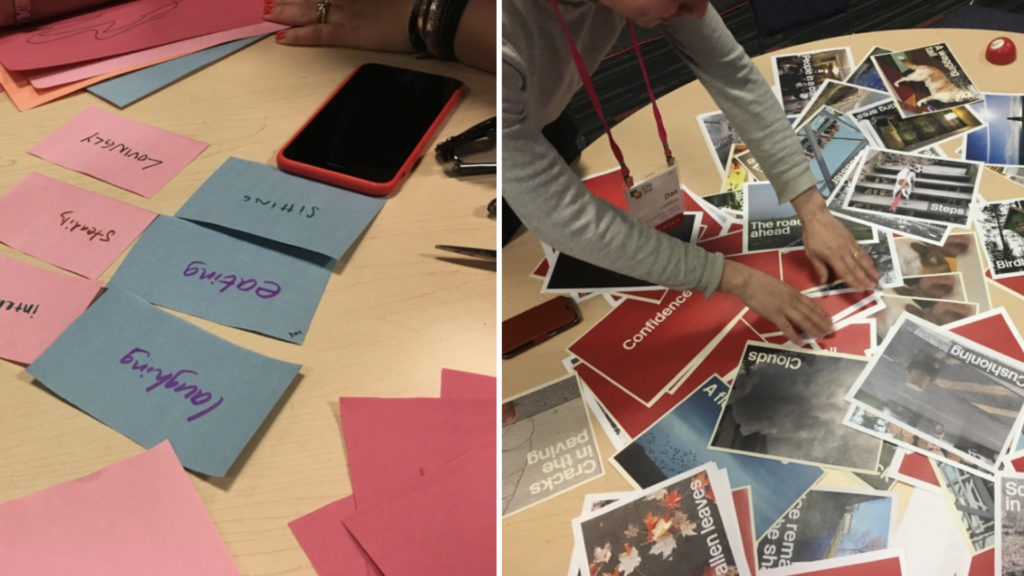

At the workshop, we split into groups and performed each-others’ recipes, gaining an embodied sense of what the receipts could produce and provoke. The images above stemmed from the recipes of Joanna Berzowska (left) and Dan Lockton (right). As a side note, Dan has gone on to make his metaphors recipe into a more formalized activity for considering and generating new metaphors that shape how designers approach their work.

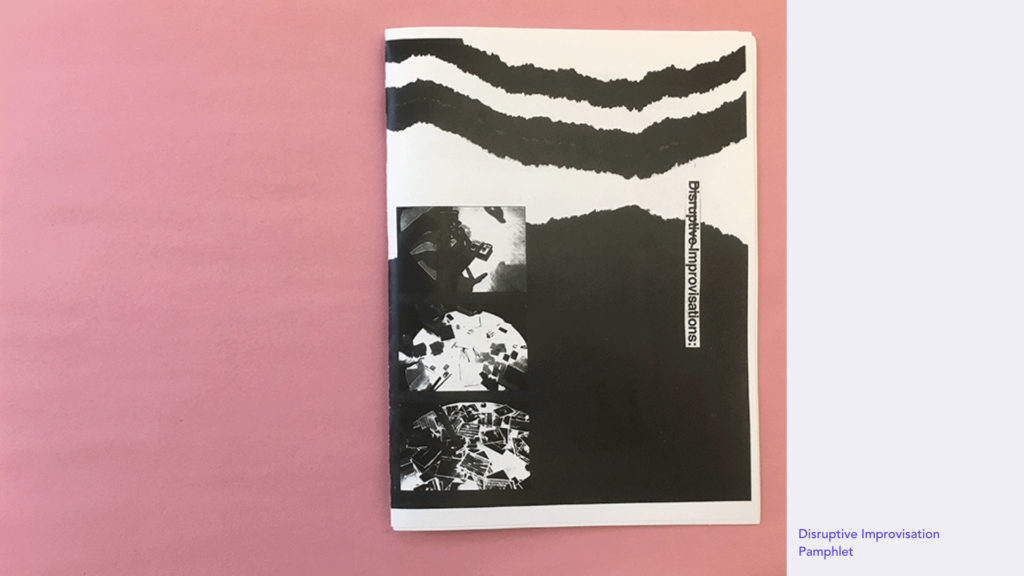

At the end of the workshop, we had each participant/group make a one-page spread about their experiences to include in an informal “zine” publication. We left the rules for this very open-ended, and each group of participants approached it in a different way – from collaboratively producing a series of dada-ist postcards to individually recording and sharing their recipe.

We collected all the spreads and took them to a copy shop, printing 100 copies that each participant could distribute at the conference.

Within the workshop, we noticed a persistent quality of participants trying to make these activities useful to HCI. The workshop format continually prompted participants to “evaluate” the techniques and to question what they might mean “for” HCI. This translated them into more actionable techniques

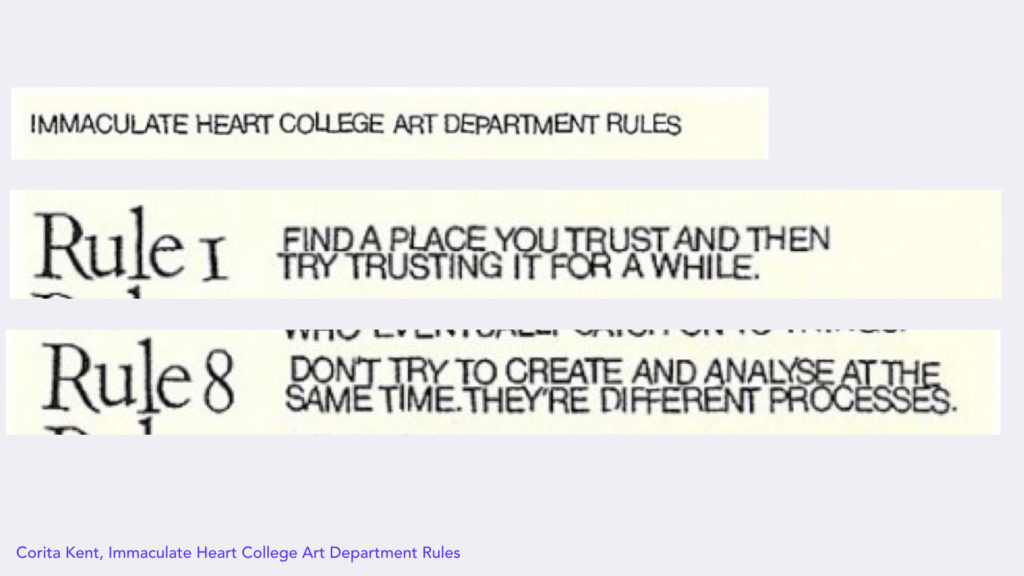

This finding made of think a bit of Corita Kent’s rules, and we felt like the workshop format broke both rule 1 and rule 8. We needed a way to create spaces for this kind of inquiry outside of the boundaries of a given topic or project. We felt that this capacity of being outside would be critical for truly letting new insights and points of attention emerge. It also created a greater space for sharing and collaborating among many diverse interests.

In an effort to go back to a bit of what we loved about the correspondence, with some of our original interest in publication formats, we decided to pursue a format of the “cookbook”

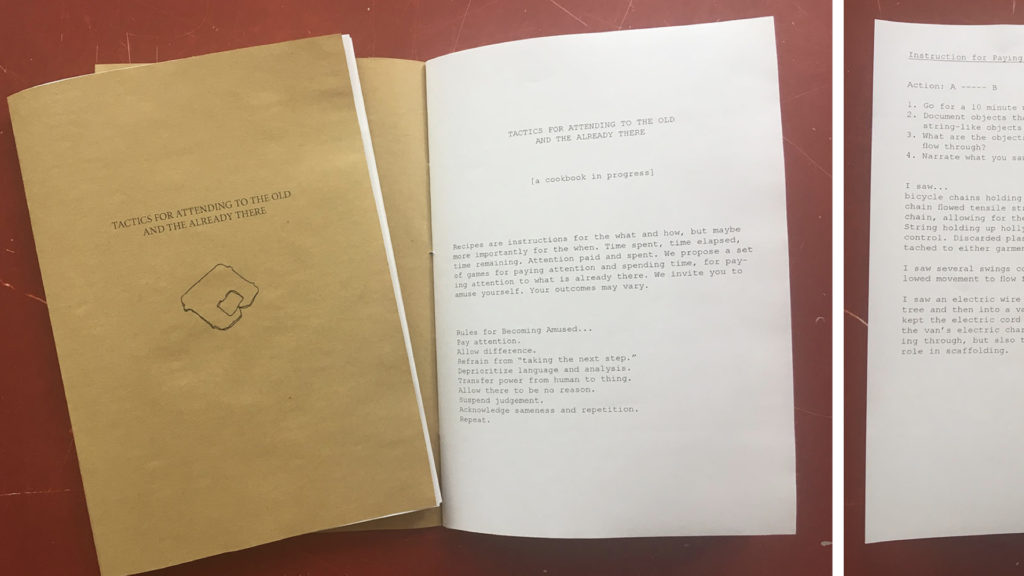

Our cookbook took shape largely with inspiration from collections of event scores like Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit. We called it a cookbook because it contained a series of recipes for making. Each author contributed a recipe to the book and we collectively performed the recipes provided by the others.

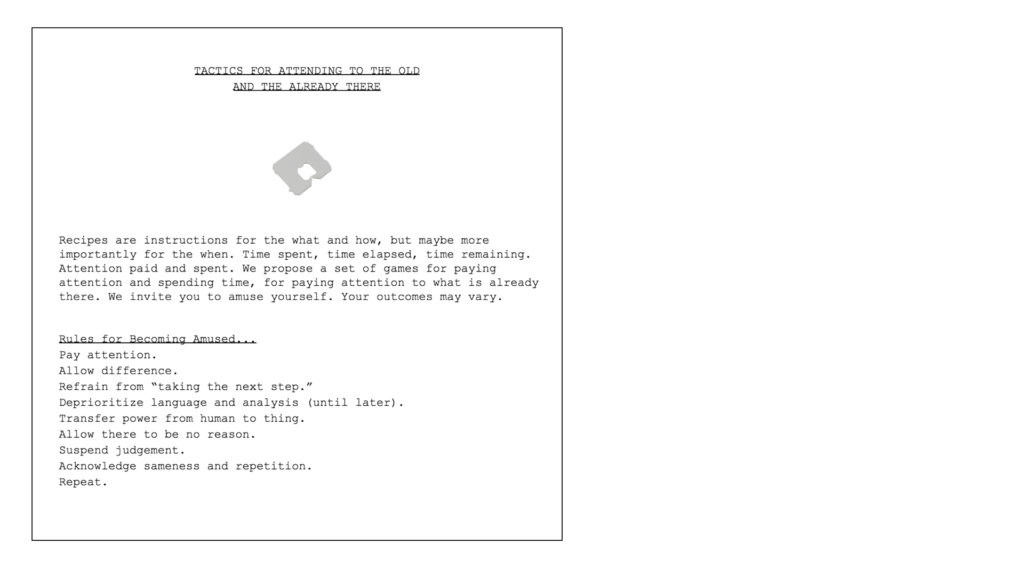

The cookbook, entitled “Tactics for Attending to the Old and Already there” contained a series of rules for “becoming amused” and each rule was complemented by a recipe for making.

We oriented each action to a theme like “allow difference” “and transfer power from human to thing”

Each author contributed an action that we each performed on our own, sharing the results.

Here is one of those recipes.

This is what happened. Bag fasteners. Always.

So in this activity, we found ourselves having our attention “curated” to some degree by each other. The interpretation and performance of the prompts led to the spawning of metaphors and metaphorical thinking—such as considering the flow of companionship through a dog leash as electricity flows through a conduit.

So where we started this thinking about what is and isn’t a contribution, we found that our non-contributions (or HCI amusements) were often deeply engaged in the old. They attended to the forgotten and overlooked yet ever present.

We began to see contributions being held together by what we called the “technological new” and the way in which the traditional focus of attention on new or emerging areas of technology, and consequences therein, allows us to more easily justify its relationship to the community. But in doing this, we turn away from a world that’s not necessary “old” as such, but made old by the focus on the new. The land of bag fasteners and desiccant packages and “non-digital tangibles” that may hold interesting resources for design and material relationships, but are more difficult to work with and then call it a contribution by traditional metrics.

The amusements could serve as a kind of “para-research” that always sits in relation to our community’s focus on the technological new, but never quite blends with it. As the gif suggests, as para-research, the amusements orbit the new.

We also began to reflect on our relationship to Fluxus, and how it helped us think about our research community from a different vantage point. And if we look to the history of interactive technology, this pattern is quite common. What was once sitting outside “orbiting” a contribution is folded into the cannon, expanding our ways of thinking, making, and evaluating.

So where we’ll conclude with amusements is by emphasizing some of their key points about their creation and exchange. We see them to be exchanged as a kind of methodological gift to be shared between one researcher and another; they legitimize seemingly random actions because they operate outside of any given goal; and they are probably not to be used with “users.” Instead, they might be thought of as probes that help us reflect on our own practices.

Will HCI-amusements solve the challenges we presented in the beginning of this project – no.

But perhaps in more actively developing means of engaging with to the mundane and taken for granted, we are hopeful we can develop new ways of seeing, connecting, and tracing our world as it unfolds.

At the very least, we hope this works creates spaces to, acknowledge and make use of our shared histories and the mutual shaping of art and technology and that a turn back to some of these histories may serve as a guide towards expanded forms of inquiry.