Weaving

The basic structure of weaving, no matter the type of loom, is the interlacing of yarns. You begin by preparing your warp yarns, or the series of tensioned that you will interlace. These are most often stretched parallel to each other but can also be arranged in other radial or triaxial patterns (more common in basket weaving). After these are stretched and of uniform tension, you weave a long thread in and out, or over and under, the warp yarns. The combination of overs and unders and the sequencing will determine the visual and structural nature of your fabric. After adding a row over and under the weft, you can beat or comb it down to form the fabric.

The structure that supports weaving is called a loom and techniques vary by the class and type of loom. As Annie Albers writes in her wonderful book "On Weaving", any woven structure can be realized on any type of loom. The different looms, thus, just make particular actions more or less efficient or allow for different lengths of yarn. I've listed looms and techniques below by complexity. This is not an exhaustive list, but ones that are more common.

| Structure | Ability to be Woven |

|---|---|

| Raw Fiber | yes, if integrated into short regions of the weft, difficult |

| Filament | yes (for warp and weft) |

| Roving & Top | yes, if integrated into the weft |

| Singles | yes (only in weft) |

| Plied Yarn | yes (warp and weft) |

| Braided Rope | yes (warp and weft) |

| Knits | yes for tubular knits, narrow flat knits, or knits rolled and/or layed flat as weft |

| Woven | yes for narrow, flat, or tubular weaves or rolled wovens into the weft |

| Non-Wovens | yes, if sliced or rolled into thin long pieces or rolled and placed in the weft |

| Solid Objects | yes, especially if they are long and narrow, if they can be threaded through the weft, or otherwise integrated at weave time into the pockets of a multi-layered structure. |

Process

Selecting Yarn and Looms

When beginning to weave, the materials and equipment are usually considered in tandem. Yarns for warping need to be durable and strong because they are placed under tension during the weaving process. Weft yarns can be just about anything, yet, for most beginning weavers, its good to start with warps and wefts that are of comparable size and materials.

The weaving density depends on the number of warp yarns per inch across the width of the loom. This is measured in "ends per inch" or epi. Weaving yarns are often soft with a suggestion of ends per inch which ought to match to your equipment. Some looms, like tapestry, rigid heddle looms, or jacquard looms, have fixed positions for you to stretch the warp into or heddles fixed at predetermined position and thus, you must find yarns to match your set up. Alternatively, you can always use less than the maximum density, so long as it still maintains the correct ratios and settings of your equipment. Other looms, like frame looms allow you to vary the density (though you typically need to find a "reed" for beating that matches your desired density). Most of the woven clothing you wear will be of a density that far exceeds what is possible on consumer grade equipment (e.g. 100 epi). Most craft weaving will consist of something around (6-20 epi)

Warping

Warping is the process of threading your loom and ensuring warp yarns are of even tension. The procedures for warping depend on the specific type of loom.

Weaving: Primary Stitches and Patterns

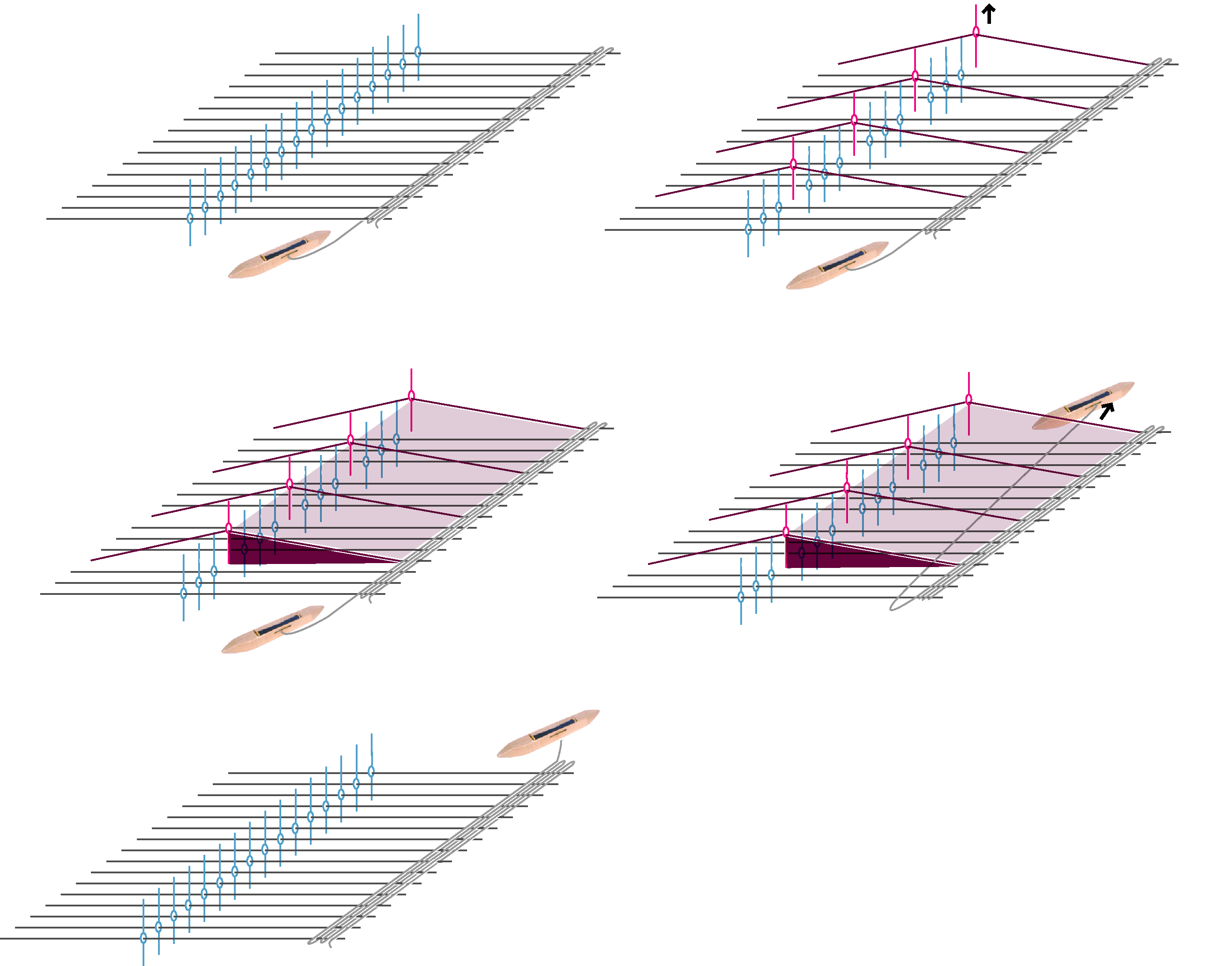

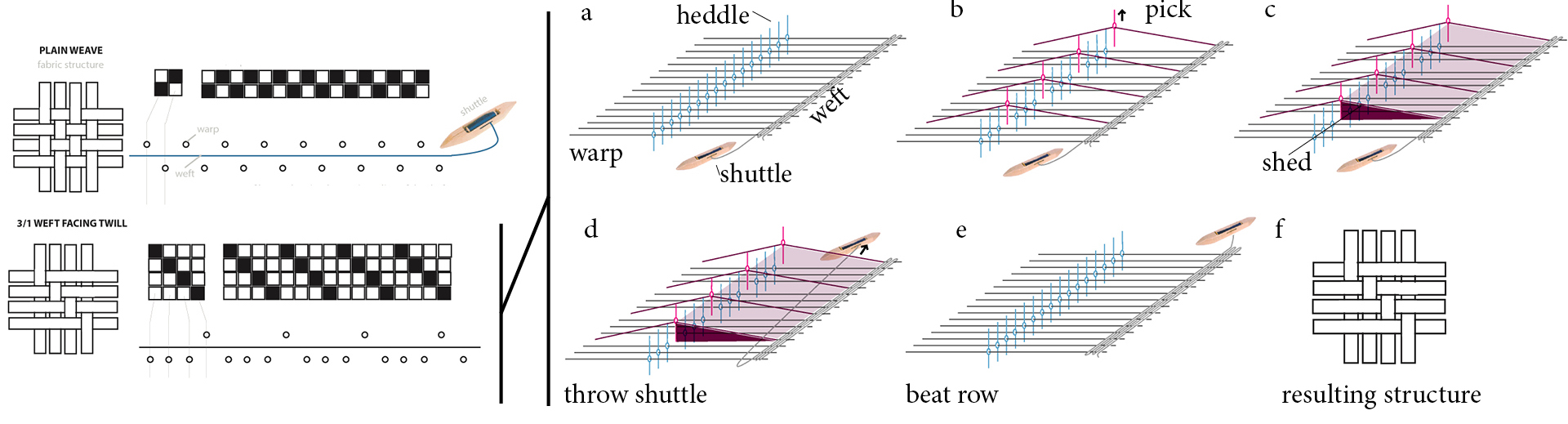

The diagram below shows the general process of weaving, particularly on a heddle based loom. An understanding of this process aids in explaining the differences in stitches and patterns.

All woven structures are created from the selection of "unders" and "overs" on any given pic. These patterns are represented by drafts that represent the minimal repeating unit that characterizes the fabric structure. If the weft travels UNDER the warp (same as: a heddle lifting that warp ), the draft square is colored solid or black. If the weft travels OVER the warp (same as: the heddle not being lifted at that warp), the draft square is colored in white or transparent. Namely, if you repeat these drafts across the weft (width) and warp (length) of your fabric, you would create a fabric made entirely of that stitch. Stitches can also be alternated or shifted arbitrarily across the length or width, depending on the loom you are using.

The ordering of these selections has infinite possibilities, but the three most basic structures are:

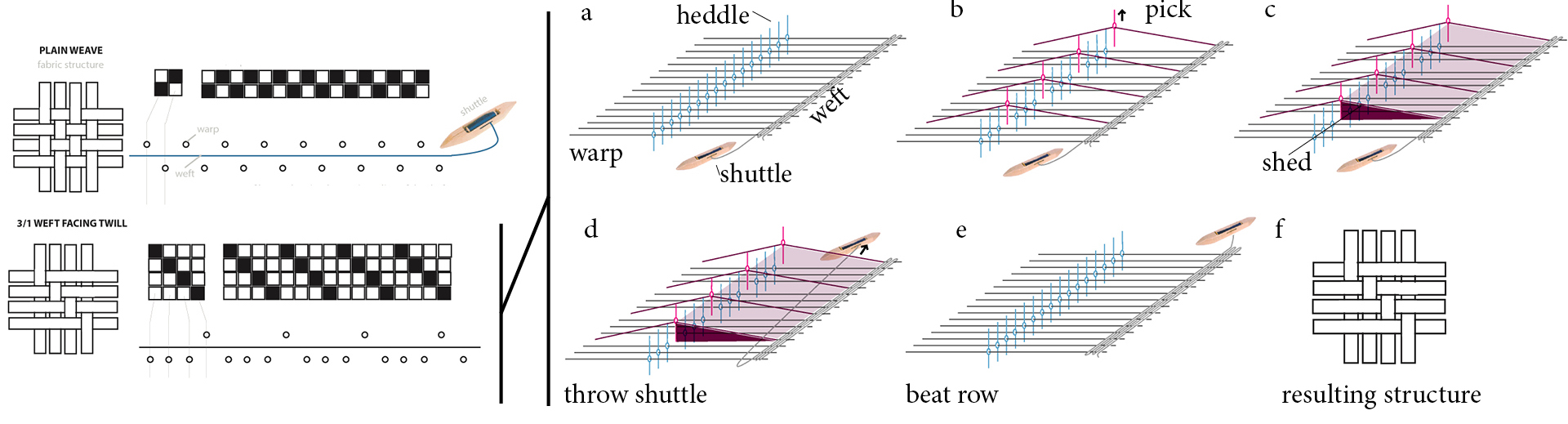

Tabby or Plain Weave: This is the weave you likely learned in school and made with paper. This is shown in the diagram above. This is where the weft alternates over and under each warp. Each row alternates the order (so if you stared with an over than under, the next row is under and then over). Tabby weaves create the most spacing between all the warps and thus the widest and thinest possible structure with any given weft yarn. Tabby weave structures are not stretchy in either direction. Weaving yarns will typically give you a suggested "set" which is how many warps of that yarn would fit in an inch of the resulting fabric.

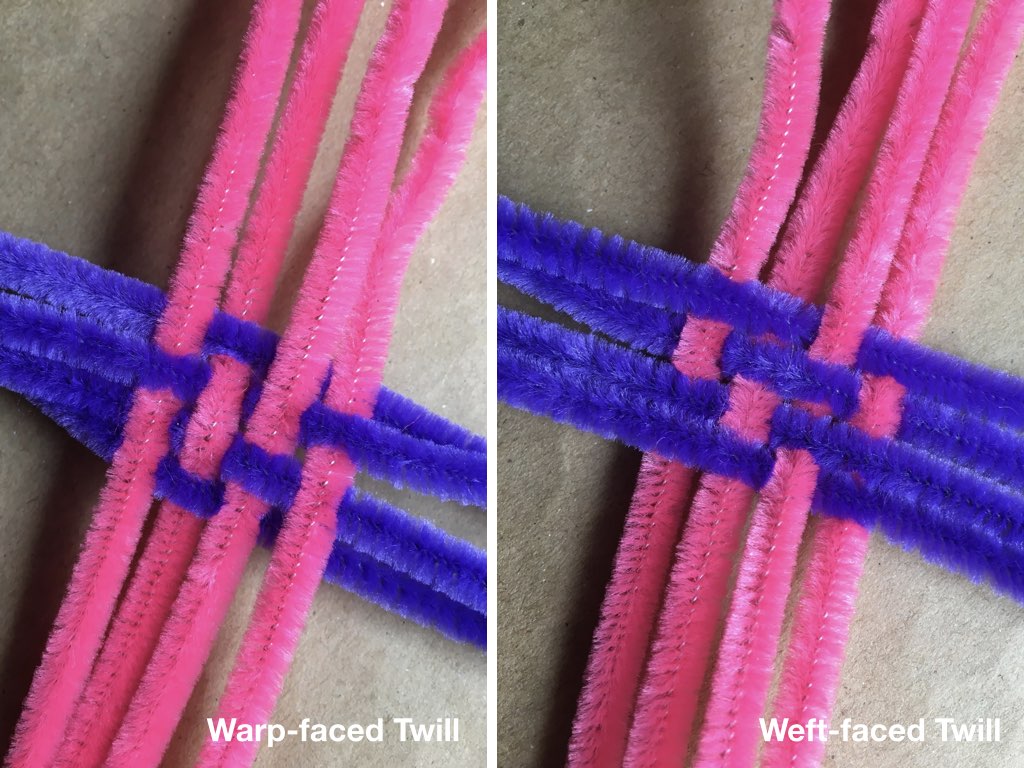

Twill: Twills are commonly seen in denim. This pattern (shown in the diagram above), consists of some repeat of overs and unders that uniformly shift position along the length, often creating visual diagonal. Twills can be balanced (meaning that they contain the same number of overs and unders each pic) or unbalanced (where the number is uneven). Unbalanced twills are called weft or warp facing depending on whether the weft travels over more or less warps respectively. The balanced or unbalanced ratio twills will allow them to pack less or more (respectively). When wefts are tightly packed, the fabric becomes thicker and more durable (which is why it is used on denim). Furthermore, twills create more textured surface structures and can vary in their amount of sheer. Unbalanced twills will also sometimes produce fabrics that curl when removed from tension. When working with different colors in the warp and the weft, the balanced or unbalanced ratio of the twill will produce different levels of shading in the resulting fabric because they modulate the ratio of warp and weft yarns that are visible on the surface. This shading will be inverted or flipped on the bottom side of the fabric.

Satin: Satin stitches are similar to twills in that they can be unbalanced at each pic, but stain weaves do not uniformly shift to create diagonal lines. Instead, the structures shifts at each row such that the interlacements (places where a series of unders go under or vice versa) are never directly next to each other. This creates long "floats" of weft yarns that pack along the surface to create softer fabrics. Satins also exhibit the same shading effects as twill, given their ratios of unbalance and can be weft-faced or warp-faced. The use of satins is typically how regions of contrasting colors are integrated into the structure of fabrics.

Many More: There are so many others, particularly waffle, basket, and birds eye stitches that have really nice properties particularly when integrating sensing.

Finishing

Finishing is the process of removing the woven fabric from the loom and fastening the ends so it does not easily unravel. The easiest finishing method (in my opinion) is quickly running the ends of the fabric through a sewing machine. Typically, long ends of the warp are exposed on the front and back ends of the fabric, and can be left as fringe, twisted into tassels, or cut off entirely.

Documenting & Patterning

Woven patterns are described by drafts, which are made using a grid structure with each cell of the grid representing the location of a warp and weft crossing each other. As such, these often describe the structure, but not the materials. A black cell denotes that the weft travels UNDER the warp at this location and a white cell denotes that the weft travels OVER the warp at this location. So if you were going to draft an entire fabric, the number of cells in the width of the draft would total number of warps in the fabric. The number of cells in the height would represent the number of pics. The convention in weaving is to represent your fabric in the smallest amount of units. Thus, if your entire fabric is made of repeating a series of pics over the width and length of the fabric, then you would represent only the repeating unit with a note at how many times it should be repeated (or let the weaver decide for themselves).

Conventions in drafting have to do with the hardware that one is using for weaving. Often, jacquard looms require each instruction to be specified (so the draft will represent the entire weave pattern). Most looms use frames to support quick weaving of repeating patterns, and thus, these drafts often represent those patterns instead of the fabric overall. The draft represents corresponds to actions on a loom and how it relates to a given structure.

Historical Connections

Weaver (1974), A Portrait of Margaret Carr

https://www.folkstreams.net/film-detail.php?id=407

1800-1900 American Hand-weaving Industry and Child Labor

Tradition Bearers (1983)

https://www.folkstreams.net/film-detail.php?id=281

Finish-American Craft History, focusing on Great Lakes Region

Navajo Weaving

The story of Spider Woman

Beauty Before Me: Navajo Weavers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_Tj4lr8i_k

A Loom with a View: Modern Navajo Weavers

2004 - Produced by Sierra Ornelas and Justin Thomas

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HkAggO4D8Og